Editor’s Note: “The Trek: A Migrant Trail to America” premieres on April 16 at 8 p.m. ET/PT on Act Daily News’s new Sunday primetime sequence, The Whole Story with Anderson Cooper.

Darién Gap, Colombia and Panama

Act Daily News

—

There is all the time a crowd, however it might really feel very lonely.

To get nearer to freedom, they’ve risked all of it.

Masked robbers and rapists. Exhaustion, snakebites, damaged ankles. Murder and starvation.

Having to decide on who to assist and who to go away behind.

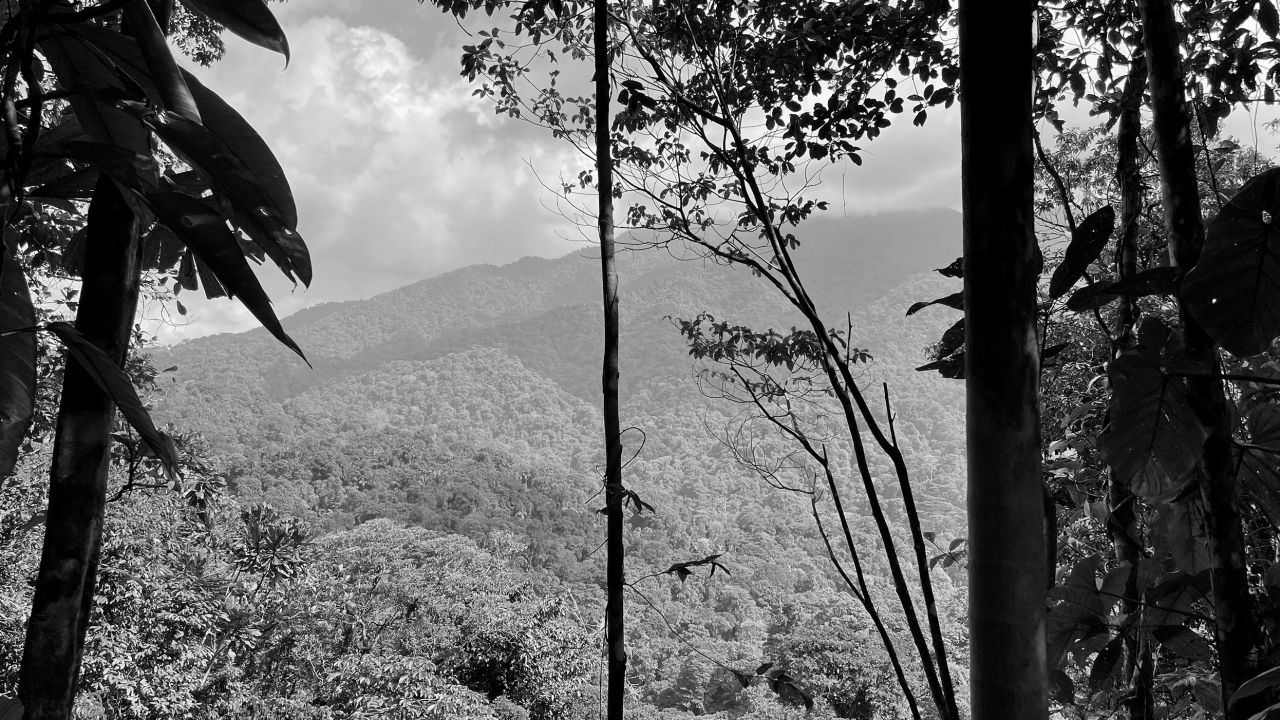

The trek throughout the Darién Gap, a stretch of distant, roadless, mountainous rainforest connecting South and Central America, is among the hottest and threatening walks on earth.

Almost 250,000 folks made the crossing in 2022, fueled by financial and humanitarian disasters – practically double the figures from the 12 months earlier than, and 20 instances the annual common from 2010 to 2020. Early information for 2023 exhibits six instances as many made the trek from January to March, 87,390 in comparison with 13,791 final 12 months, a file, in line with Panamanian authorities.

They all share the identical purpose: to make it to the United States.

And they maintain coming, regardless of how a lot more durable that dream turns into to understand.

A workforce of Act Daily News journalists made the practically 70-mile journey by foot in February, interviewing migrants, guides, locals and officers about why so many are taking the danger, braving unforgiving terrain, extortion and violence.

The route took 5 days, beginning outdoors a Colombian seaside city, traversing via farming communities, ascending a steep mountain, chopping throughout muddy, dense rainforest and rivers earlier than reaching a government-run camp in Panama.

Along the best way, it turned evident that the cartel overseeing the route is making hundreds of thousands off a extremely organized smuggling business, pushing as many individuals as potential via what quantities to a gap within the fence for migrants shifting north, the distant American dream their solely lodestar.

At nightfall, the arid, dusty camp on the banks of the Acandí Seco river close to Acandí, Colombia, hums with expectation.

Hundreds of individuals are gathered in dozens of tiny disposable tents on a stretch of farmland managed by a drug cartel, near the Colombian border with Panama. The route forward of them shall be arduous and life-threatening.

But many are naïve to what lies forward. They’ve been instructed that the times of trekking are few and simple, and so they can pack gentle.

But cash, not prayer, will determine who will survive the journey.

People are the brand new commodity for cartels, maybe preferable to medication. These human packages transfer themselves. Rivals don’t attempt to steal them. Each migrant pays no less than $400 for entry to the jungle passage and absorbs all of the dangers themselves. According to Act Daily News’s calculations, the smuggling commerce earns the cartel tens of hundreds of thousands of {dollars} yearly.

The US, Panama and Colombia introduced on April 11 that they may launch a 60-day marketing campaign geared toward ending unlawful migration via the Darién Gap, which they mentioned “leads to death and exploitation of vulnerable people for significant profit.” In a joint assertion, the international locations added that they may even use “new lawful and flexible pathways for tens of thousands of migrants and refugees as an alternative to irregular migration,” however didn’t elaborate any additional.

A senior US State Department official declined to offer a determine for cartel earnings. “This is definitely big business, but it is a business that has no thought towards safety or suffering or well-being… just collecting the money and moving people,” the official mentioned.

This money has made an already all-powerful cartel much more highly effective. This appears to be a no-go space for the Colombian authorities. Their final seen presence was in Necoclí, a tiny beachfront city miles away, filled with migrants, overseen by a couple of police.

Migrants on the Acandí Seco camp are given pink wristbands – like these handed out in a nightclub – denoting their proper to stroll right here. The degree of group is palpable and parading that sophistication could in reality be the rationale the cartel has granted us permission to stroll their route.

Act Daily News has modified the names of the migrants interviewed for this report for his or her security.

Manuel, 29, and his spouse Tamara, lastly determined to flee Venezuela with their kids, after years scrabbling to safe meals and different primary requirements. A socioeconomic disaster fueled by President Nicolás Maduro’s authoritarian authorities, worsened by the worldwide pandemic and US sanctions, has led one in 4 Venezuelans to flee the nation since 2015.

“It’s thanks to our beautiful president … the dictatorship – why we’re in this sh*t… We had been planning this for a while when we saw the news that the US was helping us – the immigrants. So here we are now. Living the journey,” Manuel mentioned. But it was unclear what assist he was referring to.

“Trusting in God to leave,” interrupted Tamara. “It’s all of us, or no one,” added Manuel, on the choice to convey their two younger kids.

Their destiny shall be impacted by Washington’s latest modifications in immigration coverage.

Last October, the US authorities blocked entry to Venezuelans arriving “without authorization” on its southern border, invoking a Trump-era pandemic restriction, generally known as Title 42. The Biden administration has since expanded Title 42, permitting migrants who would possibly in any other case qualify for asylum to be swiftly expelled, turned again to Mexico or despatched on to their residence international locations. The measure is predicted to run out in early May.

The authorities has mentioned it’ll permit a small quantity to use for authorized entry, if they’ve an American sponsor – 30,000 people per 30 days from Venezuela, Nicaragua, Haiti and Cuba.

Like many others Act Daily News interviewed, these coverage modifications had not impacted Manuel and Tamara’s determination to go north.

As daybreak drags folks from their tents, the cartel’s mechanics decide up. Christian pop songs are performed to rally these firstly line, the place cartel guides dispense recommendation. “Please, patience is the virtue of the wise,” says one organizer via a megaphone. “The first ones will be the last. The last ones will be the first. That is why we shouldn’t run. Racing brings fatigue.”

But nobody is paying consideration. Everyone is jostling as if they’re sprinters making ready to step into beginning blocks. Small backpacks, one bottle of water, sneakers – what’s comfy to maneuver with now, gained’t suffice within the days of dense jungle forward.

There is a name for consideration, a pause, after which they’re allowed to start strolling.

Sunlight reveals a crowd of over 800 this morning alone – the identical because the every day common for January and February, in line with the United Nation’s International Organization for Migration (IOM). These months within the dry season are usually the slowest on the route, as a result of the rivers are too low to ferry migrants on boats, and the massive uptick is elevating fears of extra record-breaking numbers forward.

The quantity of kids is staggering. Some are carried, others dragged by the hand. The 66-mile route via the Darién Gap is a minefield of deadly snakes, slimy rock, and erratic riverbeds, that challenges most adults, leaving many exhausted, dehydrated, sick, injured, or worse.

Yet the variety of kids is rising. A file 40,438 crossed final 12 months, Panamanian migration information exhibits. UNICEF reported late final 12 months that half of them had been below 5, and round 900 had been unaccompanied. In January and February of this 12 months, Panama recorded 9,683 minors crossing, a seven-fold improve in comparison with the identical interval in 2022. In March, the quantity hit 7,200.

Jean-Pierre is carrying his son, Louvens, who was sick earlier than he’d even began. Strapped to his father’s chest, he’s weak and coughing. But Jean-Pierre pushes on, their charge already paid. There is not any going again. Their residence of Haiti – the place gang violence, a failed authorities and the worst malnutrition disaster in many years make every day life untenable – is behind them. And inconceivable selections lie forward.

Within minutes, the primary impediment is evident: water. The route, which crisscrosses the Acandí Seco, Tuquesa, Cañas Blancas and Marraganti rivers, is consistently moist, muddy, and humid. Most migrants put on low-cost rain boots and artificial socks, through which their toes slowly curdle. They present little ankle assist and fill with water, main some to chop holes within the rubber to let it drain out.

Physical misery is a business alternative for the cartel. Once the riverbeds flip to an ascent up a mountain to the Panamanian border, porters supply their companies. Each put on both the yellow or blue Colombian workforce’s nationwide soccer jersey with a quantity, to ease identification, and cost $20 to maneuver a bag uphill – and even for $100, a toddler.

“Hey, my kings, my queens! Whoever feels tired, I’m here,” one shouts.

The route they’re strolling is new, opened by the cartel simply 12 days earlier. The fundamental, older route, by way of a crossing referred to as Las Tecas, had grow to be affected by discarded garments, tents, refuse and even corpses. The cartel, locals inform us, sought a extra organized, much less harmful different – extra alternatives to make more money.

At one among a number of huts the place locals promote chilly soda or clear water with cartel permission at a mark-up, is Wilson. Aged about 5, he has been separated from his mother and father. They gave him to a porter to hold, who raced forward.

Wilson shakes his head emphatically when requested if he’s going to the US. “To Miami,” he says. “Dad is going to build a swimming pool.” Asked about his future there, he says: “I want to be a fireman. And my sister has chosen to be a nurse.” He calls again down the path: “Papa, Papa!” His father is nowhere to be seen.

In the background is the fixed recommendation of the cartel guides. “Gentlemen take your time,” says one named Jose. “We won’t get to the border today. We have two hours of climbing left.” He urges them to utilize the stream close by, already crowded with folks. “Fill up your water. One bottle of water up there costs you five dollars,” he says pointing up the hill. “I know that a lot of you don’t have the money to buy that, so better to take your water here.”

The terrain is unforgiving, and the steep climb is especially punishing on Jean-Pierre and his sick son Louvens, for whom respiratory is audibly exhausting work. Other migrants supply options: “Perhaps he is overheating in his thick wool hat. Maybe he needs more water?” His father struggles to maneuver even himself uphill.

Six hundred meters up the slope, vivid gentle pierces the jungle cover. Wooden platforms cowl the clearing flooring, and the thrill of chainsaws blends with music higher suited to a pageant. Drinks, footwear, and meals are on sale. The route is so new, the cartel is chopping area for its purchasers into the forest as quick as they will arrive.

Tents are pitched on fallen branches. Gatorades are cheerfully offered for $4. “Keep a lookout for the snake,” one machete-wielding information warns. Dusk is a clatter of late arrivals, new tents being pitched, and makes an attempt to sleep. The subsequent day, and people after it, shall be arduous.

The second daybreak breaks and the hillside is a multitude of tents and anticipation. Water, scorching rice, espresso – folks purchase what they will, many nonetheless unaware this shall be their final probability to get meals on the route.

The measurement of the group has swollen and there’s a jostle to get into place, as they watch for the information Jose’s sign to begin. They have realized that being final means it’s important to wait for everybody forward of you to clear any obstacles.

Jose barks chilling recommendation: “Take care of your children! A friend or anyone could take your child and sell their organs. Don’t give them over to a stranger.”

As the gang strikes up the slope, the mist clings to the bushes, making the climb really feel steeper nonetheless. Some kids embrace the problem, bounding upwards playfully.

A bunch of three Venezuelan siblings make gentle work of the muddy slope collectively. “I have to hold the stick so that you guys can grab me,” says the youngest to her brother and sister. The older sister strips to her socks when the viscous mud begins claiming footwear. Their mom provides: “You’re my warrior, you hear baby?”

This morning, Louvens is wanting worse. The issue of the climb appears to have left Jean-Pierre too exhausted to totally intervene. “He’s sleeping,” he says of his slumped son, whose respiratory is labored over the sound of shoes within the mud.

Some walkers seem to have come to the jungle with little bar their will to maintain shifting. One Haitian man is sporting solely flimsy rubber footwear, a wool sweater draped throughout his shoulders, and carrying three ruffled trash baggage.

Others are propelled by the horrors of what they’ve fled. Yendri, 20, and her mom Maria, 58, left Venezuela when Yendri’s college mates had been shot lifeless in felony assaults commonplace within the nation, the place the homicide price is among the highest on this planet. “It’s so hard to live there. It’s very dangerous – we live with a lot of violence. I studied with two people that were killed.”

Her mom Maria was a professor, incomes $16 a month – barely sufficient to eat. “I’m going, little by little,” she says. “I sat down to rest and to eat breakfast so that we continue to have strength.”

Another is Ling, from Wuhan, the epicenter of the Covid-19 pandemic. He realized in regards to the Darién Gap by evading the Chinese firewall, after which researching the stroll on TikTook. “Hong Kong, then Thailand, then Turkey and then Ecuador,” he rattles off his path to the riverbank the place we meet.

“Many Chinese come here … Because Chinese society is not very good for life,” Ling provides whereas pausing to relaxation. He has additionally run out of meals already. His transfer cut up his mother and father, he says. His father was for it; his mom wished a conventional life and marriage for him. Around 2,200 Chinese residents made the trek in January and February this 12 months – greater than in all of 2022, in line with Panamanian authorities information.

The final little bit of Colombian territory grates, one father slipping as he carries his son on his again. Then the sky clears. The summit of the hill is the border between Panama and Colombia, marked with a hand-daubed signal of two flags. A cover gives some shelter, and oldsters relaxation on logs. Younger walkers take smiling selfies. There is a way of euphoria, which is able to evaporate inside a couple of hundred yards.

They are about to go away the grasp of the cash-hungry Colombian cartel and set off alone into Panama. The porters supply parting knowledge: “The blessing of the almighty is with you,” says one. “Don’t fight on the way. Help whoever is in need, because you never know when you’re going to need help.”

During this pause they will take inventory of who’s struggling most acutely. Anna, 12, who’s disabled and has epileptic convulsions, lies shaking on the chest of her mom, Natalia. “Her fever hasn’t dropped,” she says. “I didn’t bring a thermometer.”

Like many right here, Natalia says she was instructed the stroll could be rather a lot shorter – solely two hours’ descent forward, she says. The scale of the deceit has begun to emerge, and the bottom is about to actually activate them.

Once in Panama, the cartel falls away, reaching the tip of their territory, as does the agency terrain. On the opposite aspect of the border lies a steep drop down the mountain, interrupted by roots, bushes and rocks. Many stumble or slide uncontrollably. Mud grips your toes.

Maria strikes forwards slowly. “Don’t take me through the high parts,” she begs Yendri.

Natalia has requested a Haitian migrant to hold her sick daughter forward, however he quickly tires. Anna sits by the aspect of the path, alone, shivering.

The man who was carrying her has began to make a stretcher from close by canes lower from the jungle however wants assist. They can’t transfer her additional away from her mom, who’s again down the path and is aware of what Anna wants. But they can’t take her again to Natalia for assist, because the climb up has already exhausted him.

Although the path has been open for lower than two weeks, the trail is already affected by refuse. An deserted bow tie, empty tents, clothes, used diapers, private paperwork – all scattered throughout the foliage, fragments of lives deserted on the transfer.

In one clearing, there’s lastly a second of hope. Louvens, whose deterioration we had seen all through the primary days of the stroll, is alert and smiling once more after a miraculous restoration. He clambers over his father’s mates as they relaxation by the trail.

It is one other two hours’ exhausting scrabble till the sound of the water surges. The forest opens, and the jungle flooring is awash with tent poles, kids, makeshift pots and stoves. People perch on each rock within the river, the sheer quantity of migrants laid naked in a single confluence. This is simply the tail finish of this morning’s group.

There is a race to complete consuming and washing earlier than darkish. Yet even within the evening, new arrivals to the camp are cheered as they emerge from the trail.

On the third morning, the actual size of the journey comes into focus.

Jean-Pierre was instructed the entire stroll would final 48 hours. “Right now, I don’t have enough food,” he says.

Natalia, who has been reunited together with her daughter, Anna, says she was instructed the descent to the boats from the summit would final solely two days. It shall be no less than three. “‘No, your daughter can walk, this is easy,’” she says she was instructed by a Colombian information. “But it’s not… since then, all I do is pay and pay,” she sobs. She and Anna are unable to maneuver ahead and are working brief on meals.

On the winding route, chokepoints emerge at tree roots and pinnacles. Traffic jams kind, with complete households spending hours on their toes ready. In about an hour we transfer solely 100 meters.

Tempers fray. “Why can’t you hurry the f**k up bitch,” a person shouts. He is reprimanded by an older woman in the identical line, who reminds him a “proper father” wouldn’t discuss that approach.

Yet at different moments, the sense of group – of spontaneous take care of strangers – is startling. One river crossing is deep and marked by a rope. You should carry your bag overhead, and plenty of stumble. Younger Haitian males keep behind to assist others cross, forming a human chain.

But this generosity can’t assist with the bodily ache or blunt the anxiousness about what lies forward.

Standing on the riverbank, watching others stumble via the water, Carolina, from Venezuela, weeps. “Had I known, I would not have come or let my son come through here,” she says. “This is horrible. You have to live this to realize crossing through this jungle is the worst thing in the world.”

Exhaustion is starting to dictate each transfer. We cease subsequent to the river to camp, and after an hour the positioning is overflowing with migrants, searching for security in numbers and a pause. Dusk is setting in.

In one of many tents is Wilson, the five-year-old. He has reunited along with his mother and father once more, who caught up with him on the route. His father says his son is in good well being, regardless of having surgical procedure 9 months earlier.

Outside one other tent is Yendri, tending to her mom, whose proper hand is uncooked with blisters after strolling with a stick and moist leather-based gloves. She and Maria are additionally out of meals, having given it away to different migrants, as they too thought the trek was simply two or three days lengthy.

But deprivation just isn’t new to so many on the riverbank. Venezuelans discuss across the campfires of ready in line from 1 a.m. to purchase groceries however leaving empty-handed at 6 p.m.

“You’d get to the end of the line and there was no food. Nothing. We’d last two, three nights and that’s when I decided [to leave],” Lisbeth, a mom from Caracas says, as she begins to cry.

Some even joke they’re consuming higher within the jungle than within the Venezuelan capital.

The subsequent morning, the migrants cross a black plastic cover stretched throughout 4 poles. Locals inform us that earlier than this new route opened, it was an in a single day cease for thieves. It’s near Tres Bocas, a busy confluence within the rivers, the place an previous migrant route meets this new one.

The two routes at the moment are, it appears, competing, with security and pace their rivaling commodities. Locals inform us the cartel has been combating internally and fracturing. The new path was created as a part of that fissure, however it’s unclear whether or not it will likely be any safer. Known as one of many world’s most harmful migrant routes, the Darién Gap exposes those that cross it not solely to pure hazards, however felony gangs recognized for inflicting violence, together with sexual abuse and theft.

The crowds fall away on the mouth of the previous route, a riverbed resulting in Cañas Blancas, a mountain crossing into Colombia. It’s lined with trash – ghostly plastic hangs from the bushes, left there when the river flowed increased in wet seasons previous.

Clothes are nonetheless hanging from swiftly erected washing traces. A baby’s doll and rucksack lie deserted. The density of refuse displays the quantity of people that’ve walked the route over the past decade – a few of whom didn’t make it out.

We quickly come upon a couple of of them. A corpse sporting a yellow soccer jersey and wristband, his cranium uncovered. Further up the trail, a foot will be seen protruding from below a tent – a makeshift cross left close by in hurried memorial. Elsewhere, the physique of a girl, her arm cradling her head. According to the IOM, 36 folks died within the Darién Gap in 2022, however that determine is probably going solely a fraction of the lives misplaced right here – anecdotal experiences counsel that many who die on the route are by no means discovered or reported.

Another mile upstream is what seems to be a criminal offense scene. Three our bodies lie on the bottom, every about 100 yards from one another. The first is a person, face down on the roots of a tree, rotting on a pathway. The different two are ladies. One is inside a tent, on her again, her legs unfold aside. The third is hid from the opposite two behind a fallen tree alongside the riverbank. She lies face down, discovered by migrants, in line with pictures taken three weeks earlier, together with her bra pushed up round her head. There are accidents round her groin and a rope by her physique.

A forensic pathologist who studied pictures of the scene at Act Daily News’s request and didn’t wish to be named discussing a delicate situation, mentioned there have been doubtless indicators of a violent demise within the case of the one girl with a rope close to her physique, and the opposite two our bodies – the person and girl – doubtless, “did not die of natural causes.”

Yet there’s unlikely to be an investigation. Panamanian authorities had been instructed by journalists in regards to the incident weeks prior, however there is no such thing as a indication they’ve been right here. Migrants simply stroll by the scene, a cautionary story. No graves, only a second of respect – afforded by discarded tent poles, customary right into a cross.

Nearby is Jorge, who’s on his second bid to cross into the US, the place his brother lives in New Jersey. His first try ended with deportation again to Venezuela. Both of his journeys have been marred by violence. Just days earlier, additional up the previous route close to the Colombian border, males in ski masks robbed his group.

“When we were coming down Cañas Blancas, three guys came out, hooded, with guns, knives, machetes. They wanted $100 and those that didn’t have it had to stay. They hit me and another guy – they jumped on him and kicked him,” he mentioned, including the group needed to borrow from different walkers to pay the $100. “That’s the story of the Darién. Some of us run with luck. Others with God’s will. And those that don’t pass, well they stay and that’s the way of the jungle.”

At evening, discuss of the violence and theft spreads via the group. Their tents are pitched nearer collectively, and so they burn plastic to warmth meals, choking the air, at instances risking catching the bushes alight.

The closing hours of the stroll, that subsequent daybreak, see nice sacrifice among the many migrants. And with the tip in sight, no person is prepared to go away anybody else behind.

Along one riverbed, a crowd has fashioned round a Venezuelan man in his early 20s, named Daniel. His ankle has swollen pink from damage. Of the ten days he’s spent within the wild, he’s been right here for 4.

Other Venezuelans are busy round him, discovering meals and medication. One injects him with antibiotics. Four different males, strangers to Daniel till half-hour earlier, style a stretcher from close by branches, and carry him on, always joking amongst themselves. “That man is crazy. In the US, don’t they have psychologists to help this guy?” one says.

A girl from Haiti, Belle, is 5 months pregnant and quiet. She is shaking from starvation and thirst. She too will get assist – meals and water from different migrants.

Anna, the 12-year-old woman who’s disabled, and was stranded on a hillside after being separated from her mom, continues to be shifting forwards. For a day now, she has been carried on the again of 1 man: Ener Sanchez, 27, from a Venezuelan-Colombian border city. Exhausted, he says: “I have to wait for her mother because we can’t leave her.”

The warmth is excessive, and the boats seem to all the time be additional than imagined alongside the rocky, impassable riverbed. One Haitian girl lies on the trail, water poured on her head by mates to chill her down.

And once they lastly attain the boats, their ordeal just isn’t over, however prolonged. Lines curve alongside the riverbank for every canoe – wood vessels generally known as “piraguas” crammed stuffed with migrants every paying $20 a head. The boats arrive always, maybe six at a time, to cater to the amount of migrants – every making $300 when full.

Fights get away among the many exhausted over who’s first in line. A medical rescue helicopter passes overhead, the primary signal of a authorities presence since we entered Panama three days earlier.

Carolina is right here, making an attempt to board. Fatigue overshadows her aid. “Nobody knows but this jungle is hell; it’s the worst. At one point on the mountains, my son was behind me, and he would say, ‘Mom, if you die, I’ll die with you.’” She says she instructed her son to chill out. “My legs would tremble, and I would grab on to tree roots. There was a moment when the river was too deep for me. I saw my son put a child on his shoulders and he told me, ‘Mom, I am going to help. Don’t worry, I am okay.’”

“I regret putting my son through this jungle of hell so much that I have had to cry to let it all out because I risked his life and mine,” she provides, gazing towards the river.

The boats wrestle to drift, every too weighed down by passengers within the shallow water of the dry season. Only when some migrants get out to push can they progress, and even that causes a jam. They cross a human cranium on a log. And an hour down the river, they arrive in Bajo Chiquito, the primary immigration station in Panama, the place they’re provided first help, primary companies and are processed by authorities.

The government-run station just isn’t designed for this many. Processing is supposed to take a matter of hours earlier than they’re moved to camps whereas they await passage onwards to Costa Rica, Panama’s neighbor to the north. But many are caught right here with the backlog. Sodas value $2. Some hurriedly purchase new footwear or flip-flops for $5.

Even in case you are fortunate sufficient to go away this crowded middle, there is no such thing as a respite. Panamanian authorities are eager to point out us two migration reception facilities, which wildly differ.

One is San Vicente, a not too long ago renovated facility with home windows, clear beds, and plumbing, that separates ladies from males. Water springs from the taps and shade from the solar is plentiful. The solely complaints we hear are between completely different nationalities about who’s handled higher. But it hasn’t all the time been this good.

The camp was talked about in a UN report launched in December of final 12 months, which strongly criticized the circumstances in Panamanian immigration facilities and even accused Panamanian officers of soliciting sexual favors from migrants in change for a seat on the buses headed north.

According to the report, the UN acquired complaints that staff from the SNM [National Migration Service of Panama] and SENAFRONT, the Panamanian nationwide border power, “requested sexual exchanges from the women and girls housed in the San Vicente Migration Reception Center who lack the money to cover the aforementioned transportation costs, with the promise of allowing them to get on the coordinated buses by the Panamanian authorities so that they can continue their journey to the border with Costa Rica.”

The Panamanian authorities didn’t reply to Act Daily News’s request for touch upon allegations that SNM and SENAFRONT staff sexually exploited ladies and women at San Vicente.

The different camp, referred to as Lajas Blancas, is an extension of the migrants’ struggling. There, the subsequent day, we meet Manuel and Tamara once more.

Lajas Blancas additionally can’t address the numbers. Lines kind for lunch, but a loudspeaker quickly says parts have completed. The couple obtained right here early within the morning, strolling at evening from Bajo Chiquito. Now they’re reeling from how poor the circumstances are on this place they’ve fought to achieve. Buses go from right here to the border when you’ve got the cash.

“When I got here in the early morning, only four buses left,” Manuel says. Next to him, one among his sons vomits onto the plastic mattress they’re all making an attempt to relaxation on. “The oldest, 5-year-old, has diarrhea, fever and [has been] throwing up since yesterday. Our 1-year-old has heat stroke. All that we want is a bus,” he says.

Other migrants have endured weeks on the camp, some even working as cleaners in filthy circumstances to earn a seat on a bus. “They put us to clean two weeks ago,” mentioned a Colombian man of the camp, which is run by SENAFRONT. “But the buses came last night, and they took everyone with money.”

SENAFRONT didn’t reply to Act Daily News’s request for remark concerning the circumstances at Lajas Blancas.

A pregnant girl provides: “We’ve been here for nine days. I’ll be close to giving birth here. They don’t give us answers. They have us working and don’t give us a ‘yes, it’s [time] for you to leave.’ In the end, they lie to us.”

Diarrhea, lice, colds – the complaints develop. They level in direction of the appalling hygiene of the bathe blocks, the place soiled water simply drains onto the bottom outdoors. The close by wash basins are worse: no water and human feces on the ground.

“The whole point of surviving the jungle was for an easier way forwards, and now all we are is stuck,” says Manuel. “I was starting to have nightmares. My wife was the strong one. I collapsed.”

Their dream of freedom should wait, for now changed by servitude to a system designed to make them pay, wait, and threat – every in sufficient measure to empty their money slowly from them, and maintain them shifting ahead to the subsequent hurdle.

Source: www.cnn.com