On a biting chilly morning on November 28, 1972, a Frenchman was guillotined for a homicide he didn’t commit, in a case that so traumatized his lawyer he would spend the remainder of his life campaigning to finish the demise penalty. Roger Bontems, 36, was beheaded for being an adjunct to the brutal homicide of a nurse and a guard throughout a break-out try at a jail in japanese France.

Seven minutes after he was decapitated within the courtyard of La Sante jail in Paris, his co-conspirator Claude Buffet — a 39-year-old man convicted of a double homicide that had despatched shockwaves by means of France — met an identical finish.

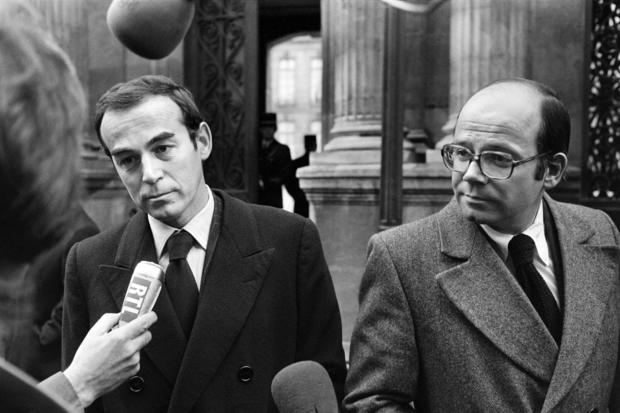

STF/AFP through Getty Images

Among the witnesses of the executions was Robert Badinter, a crusading younger lawyer who was haunted by his failure to save lots of the lifetime of his shopper Bontems.

In a 2002 interview, Badinter, who as justice minister famously defied a hostile French public to abolish capital punishment in 1981, revealed that for a very long time after Bontems’s demise, “on waking around dawn, I would obsessively mull over why we had failed.”

“They had accepted that he had not killed anyone. Why then did they sentence him to death?”

In September 1971, Buffet, a hardened felony who’s serving a life sentence for homicide at Clairvaux jail, convinces fellow inmate Roger Bontems, who’s serving a 20-year time period for assault and aggravated theft, to affix him in a high-stakes escape try.

The pair faux sickness and are taken to the infirmary the place, armed with knives carved out of spoons, they take a nurse and a guard hostage.

They threaten to execute their captives except they’re freed and given weapons.

This precipitates a standoff with the authorities that retains the French glued to their TV screens till police storm the jail at daybreak and discover each hostages useless, their throats slit.

“The murderers’ lawyer”

The grisly homicide of the nurse, a mom of two, and the jail warden, father of a one-year-old lady, sparks an impassioned debate concerning the demise penalty, which has not been carried out since President Georges Pompidou, a realistic Gaullist, got here to energy two years earlier.

Hundreds of individuals baying for the mens’ heads pack the streets outdoors the courthouse after they go on trial in Aube in 1972. The nurse’s husband and warden’s household are amongst these attending.

Buffet, who’s portrayed within the media as a heartless monster, admits to killing the guard and stabbing the nurse, and defies the court docket to condemn him to demise.

Bontems is discovered responsible of merely being an adjunct. But he’s additionally given the demise penalty, amid intense stress from jail wardens’ teams searching for revenge for his or her colleague’s demise.

Badinter appeals to the best court docket within the land to not apply the legislation of “an eye for an eye,” after which to Pompidou, who has pardoned six different death-row prisoners.

-/AFP through Getty Images

His pleas fall on deaf ears within the face of a ballot displaying 63% of the French favor capital punishment.

On November 28, 1971, Bontems and Buffet are beheaded within the courtyard of La Sante jail, below an enormous black cover erected to stop the media snapping footage from a helicopter.

Badinter, whose Jewish father died in a Nazi demise camp, would later say the case modified his stance on the demise penalty “from an intellectual conviction to an activist passion.”

“I swore to myself on leaving the courtyard of la Sante prison that morning at dawn, that I would spend the rest of my life combatting the death penalty,” Badinter instructed AFP in 2021.

Five years later he helped persuade a jury to not execute a person who kidnapped and murdered a seven-year-old boy, in a case that he was a trial of the demise penalty itself.

Badinter referred to as in consultants to explain in grisly element the workings of the guillotine, which had been used to decapitate prisoners for the reason that French Revolution of 1789.

In all, he saved six males from execution, eliciting demise threats within the course of.

“We entered the court by the front door and once the verdict had been read and the accused’s head was safe, we often had to leave by a hidden stairway,” the person dubbed “the murderers’ lawyer” by his detractors, recalled.

When he was appointed justice minister in President Francois Mitterrand’s first Socialist authorities in June 1981, he made ending the demise penalty an instantaneous precedence.

Its abolition was lastly adopted by parliament on September 30, 1981, after a landmark tackle by Badinter to MPs.

Decrying a “killer” justice system, he stated: “Tomorrow, thanks to you, there will no longer be the stealthy executions at dawn, under a black canopy, that shame us all.”