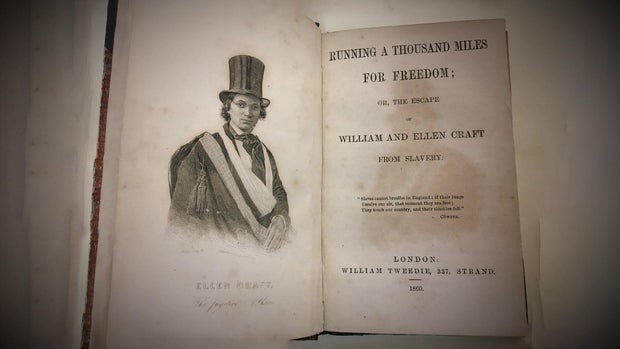

Inside the Boston Public Library, deep within the stacks, are clues to an escape from slavery in 1848 – a panoramic mixture of daring and deception. Author Ilyon Woo, who has spent the final seven years combing by way of archives from Georgia to Massachusetts, confirmed “Sunday Morning” an illustration of Ellen Craft, an engraving primarily based on a daguerreotype picture. “There’s just something magical when you hold this paper in your hands,” she mentioned.

CBS News

Ellen Craft was an enslaved girl and seamstress dwelling in Macon, Georgia, within the 1840s. She was the daughter of an enslaved girl who had been impregnated by her White enslaver. “When Ellen Craft was 11 years old, her mother, Maria, had to watch as her daughter was given away as a wedding gift to her enslaver’s oldest daughter – her half-sister,” Woo mentioned.

In her early 20s, Craft married an enslaved man, William Craft, a talented cabinetmaker. “They were afraid to have children in slavery,” mentioned Wood, “because their enslaver could reach down into the cradle that they had made for their child and take their child away. And there’s nothing they could do in the slave system in order to stop that.”

They got here up with a daring plan: Ellen would disguise herself as a rich White man who was touring with “his” enslaved particular person: her husband, William. They would escape to the North in plain sight.

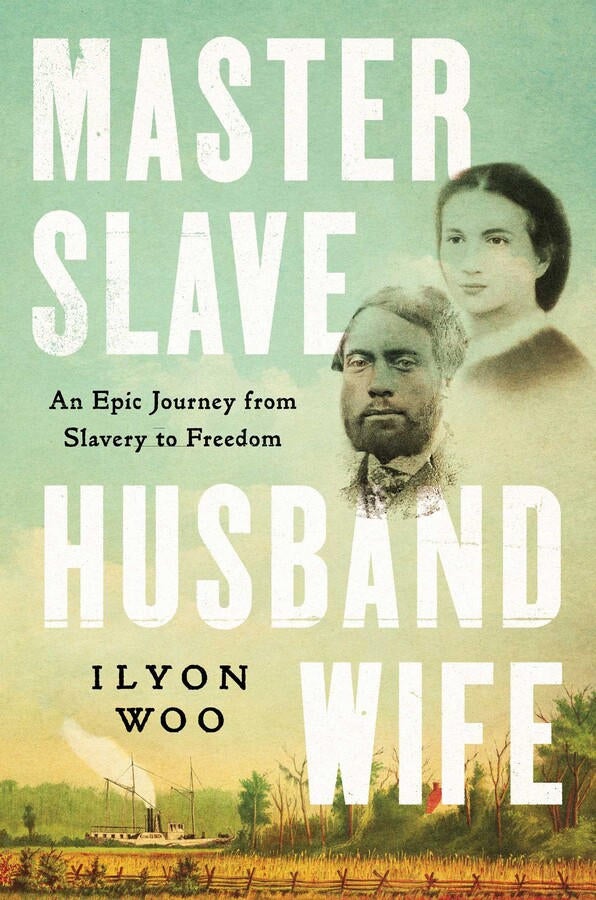

Woo lays out the Crafts’ story in her new guide: “Master Slave Husband Wife,” printed by Simon & Schuster (a part of CBS’ dad or mum firm, Paramount Global).

Simon & Schuster

“She put on this disguise to conceal both her gender and her race,” mentioned Woo. “And to that, she added disability. She knew that she would have to sign for William, as her slave, at various hotels and other stops. And she couldn’t do that because she’d been denied literacy. And so, she had to figure out how to get somebody else to sign for her or avoid that situation. So, she puts her arm in a sling. And she also puts poultices on her face. It almost serves as a kind of a mask.”

The Crafts made their method from Macon by way of the South, on trains and steamboats, heading off challenges from passengers and ticket brokers. It all virtually led to Baltimore, the final cease earlier than the North. An officer confronted them, and Ellen argued again, saying “You have no right to detain us here.”

“Finally the official says, ‘All right, I’ll just let you go,'” mentioned Woo.

“So, it’s almost like a wartime border crossing?” requested Whitaker.

“Yes!”

As a baby, Peggy Trotter Dammond Preacely discovered about her great-great-grandparents’ unimaginable journey. “As Black people in America, we have to wear a mask often,” she informed Whitaker. “We can’t always allow people to know what we’re thinking. So, this masking, and this disguise, and this ability to be in the room and absorb, was so incredible that it enabled them throughout their four days of escape to encounter certain situations and figure out what to do.”

The Crafts traveled first to Philadelphia, then Boston, the place they turned the toast of the abolitionist group. They spoke at historic Faneuil Hall, and have become a part of a street present that includes abolitionists like William Wells Brown and Frederick Douglass.

The Crafts stayed at a home in Boston’s largely Black Beacon Hill neighborhood. But the hazard wasn’t over. The public consideration alerted their former enslavers, who despatched so-called “slave-hunters” up North to seize them. Congress had simply handed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which required the general public to assist seize enslaved individuals who escaped.

But the abolitionist group in Boston wasn’t having it. The slave-hunters had been harassed, each by rock-throwing crowds and the authorized system.

According to Woo, “There were lawsuits against the slave hunters so that they would keep them busy, and there were smaller, pettier arrests as well. They would get arrested for chewing tobacco or driving too fast.”

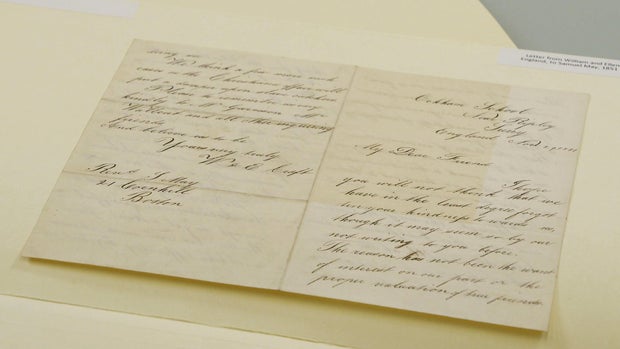

The slave-hunters fled from Boston. But the Crafts nonetheless did not really feel secure. They uprooted their lives once more, this time crusing to Halifax, Nova Scotia, after which to Liverpool, England. There, they lastly discovered to learn and write.

CBS News

In addition to letters to supporters, they wrote the story of their escape, “Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom,” printed in 1860.

Woo mentioned, “Almost as soon as they arrive in a safe space, they do pursue their twin dreams: One is literacy and learning, and the other is to have a free-born child.”

About a 12 months after their arrival, they’d their first youngster, Charles Estlin Phillips Craft. Altogether Ellen and William raised 5 kids.

Great-great-granddaughter Peggy Preacely mentioned, “I believe that legacy of the Crafts is really a part of all of our family, all of the descendants.” She channeled that legacy into civil rights advocacy, placing her on the heart of the motion within the Sixties, becoming a member of marches within the South. She confirmed Whitaker a photograph of her attending a Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee/Albany Freedom Movement occasion in Albany, Ga., in 1962: “We were jailed twice while we were there, once in a stockade. And it was my third time in jail in the movement.”

CBS News

Preacely can also be a poet, and has used poetry to maintain the daring spirits of Ellen and William Craft alive:

Today, we stand,

our household in a perpetual circle of grace.

Listening to our ancestors,

calling to us by way of blood and sacrifice and communal area,

to rise, proceed, rejoice,

and persist on this continuum

of collective effort and particular person sacrifice.

Following their steppingstones to liberation.

READ AN EXCERPT: “Master Slave Husband Wife” by Ilyon Woo

For extra data:

Story produced by Alan Golds. Editor: Ed Givnish.

See additionally: